For some owner-operators, it looks like the end of the road

More than a third in FreightWaves Research survey say they’ll leave industry if H2 doesn’t rebound

In an article posted by Fright Waves, Joe Antoshak discusses the real reasons behind many owner-operators wanting to leave the freight industry:

“The current market is tough enough for owner-operators that a significant chunk of them are considering leaving it altogether.

At least that’s according to a recent FreightWaves Research survey. When asked to select statements that applied to them, 35.2% of self-identified owner-operators checked, “If the market does not rebound materially by the end of 2023, I will leave the industry.” Meanwhile, about 21% said they were having trouble finding loads to haul, suggesting woes weren’t primarily volume related — at least not yet. Fewer than 8% said they were considering signing on with a larger carrier.

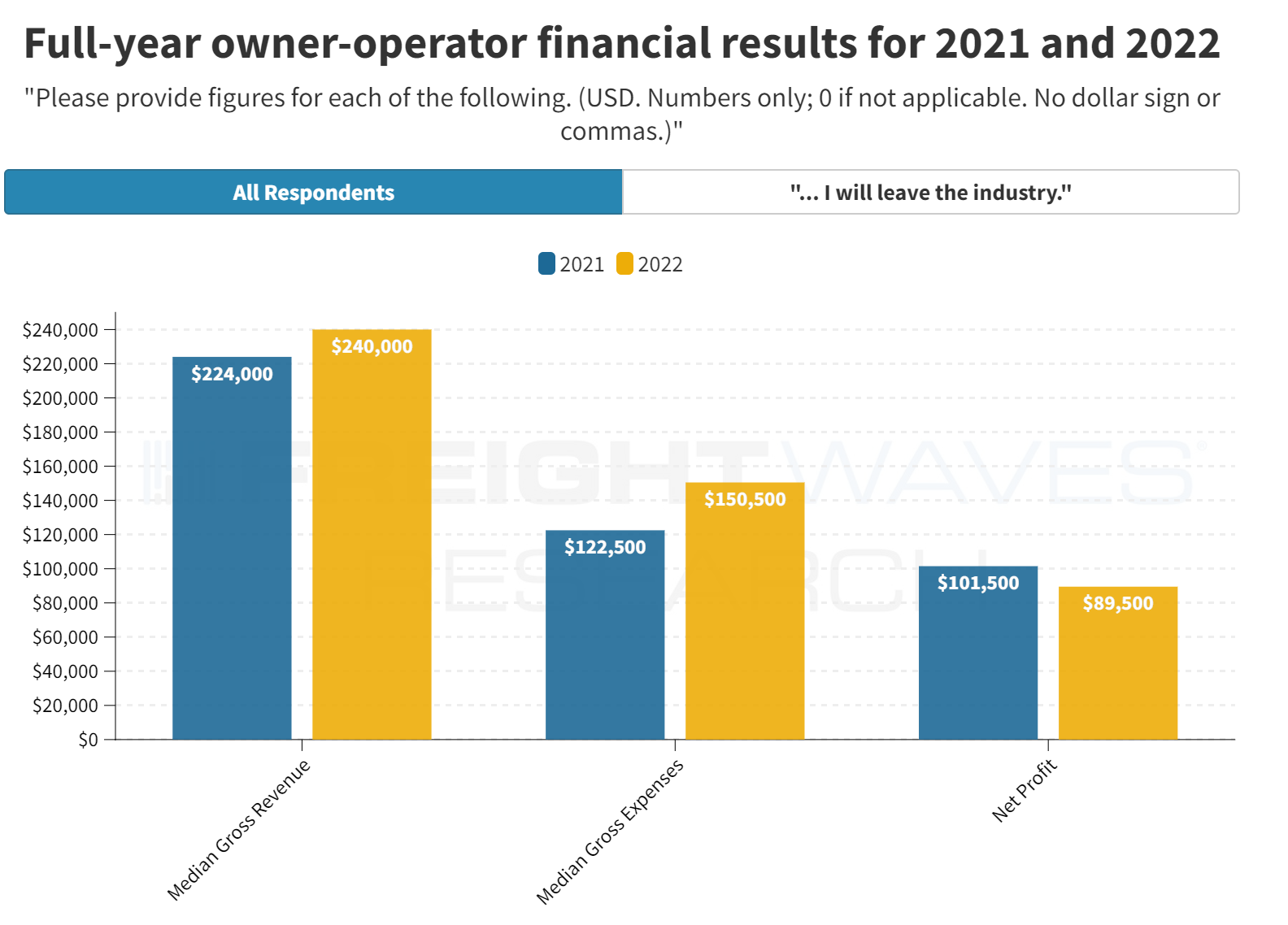

It’s no wonder that owner-operators are having a tough time. Last year saw a brutal convergence of sky-high fuel, equipment and insurance costs, all while spot market rates dashed downward. The median owner-operator in this survey did see revenue grow 7% from 2021-22 — from $224,000 to $240,000 — but expenses far outpaced that success. They paid 22.9% more to operate in ’22.

As could be expected, that trend is exacerbated when looking just at respondents who said they were ready to hang it up. Interestingly enough, that group saw stronger revenue growth year over year (y/y), earning $215,950 in 2022 (9.3% growth). But expenses spun out of control to $152,500, a 38.6% increase).

Somewhat more positively, the most common answer was “I have seen profit margins decrease, but my business is still sound,” which garnered 47.3%. When asked to indicate on a sliding scale from 0 to 100 how they would rate the current state of their business — where 0 indicates imminent bankruptcy and 100 indicates rapid growth — the average number was about 47, which leans negative but is just about neutral.

FreightWaves targeted the survey at owner-operators from Feb. 9-17 and heard from roughly 120 carriers in all. More than three-quarters of those identified as owner-operators, and another 6.7% answered “no, but I was for part of 2022.” Only results from current owner-operators were considered in the analysis.

The results reiterate that the drop-off in trucking demand over the last 12 months has hit smaller carriers particularly hard, since their business models tend to be less diversified and have less flexibility to weather profit-margin cuts. In times like these, larger carriers can outbid smaller ones on lanes in order to keep trucks moving. And while the seasoned owner-operator might be able to park their truck in response, the rookie owner-operator likely doesn’t have that option.

It’s difficult to gauge how much capacity would need to leave the market for supply and demand to meet at the middle, but this pressure figures to play a part in tightening the market over the next 12 months.

High tide, low tide

According to the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, about 350,000 to 400,000 truck drivers in the U.S. and Canada are owner-operators. Roughly 150,000 are members of OOIDA, which lobbies for their interests as its primary responsibility. The average owner-operator has been driving for more than 20 years, and this downturn will likely not force that driver out of the industry, at least not against their will.

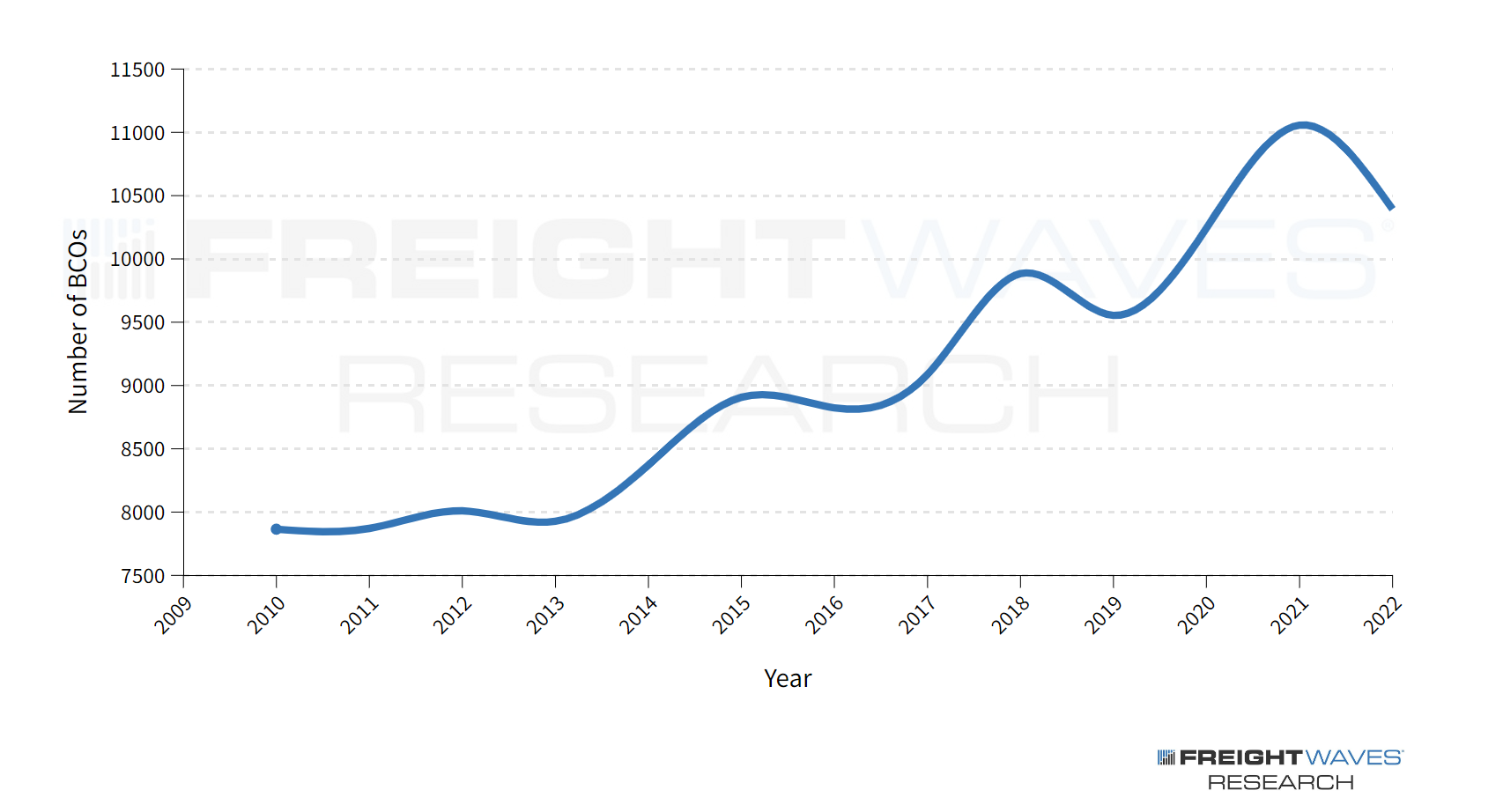

It’s the new owner-operator that’s most at risk, and trucking has a lot of them these days. OOIDA distinguishes between driver members who lease on to larger fleets with those who operate under their own individual authority. Sometime around the middle of 2020, the association experienced a first: It had more own-authority members than lease-on. Drivers wanted to take advantage of the high demand and climbing spot rates while they could.

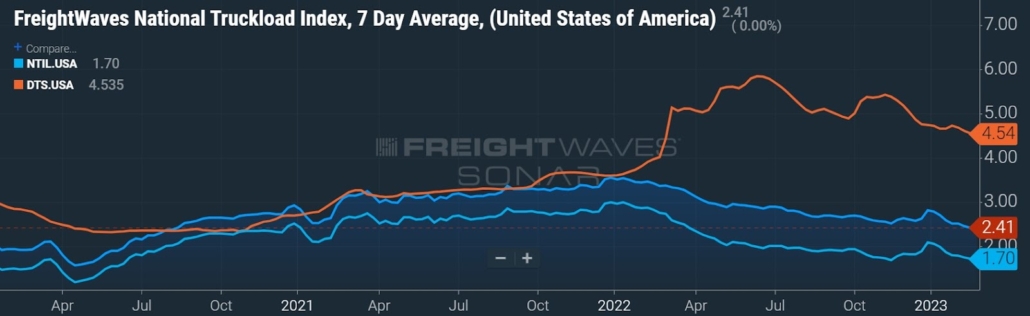

That high rate of member drivers securing their own authority carried on right up until March 2022, according to Andrew King, research analyst at OOIDA. At that point the new own-authority members dropped off, along with spot market rates.

On Feb. 22, the OOIDA Foundation will publish results from its own owner-operator survey that paint a similar picture to those in this survey. Once public, you’ll be able to find them on the foundation’s recent research page. Among the varied results, the survey found that overall operating costs per mile climbed from around $1.75 in 2020 to about $2.35 in ’22 — an increase of more than 30% in two years.

“[This downturn is] definitely more severe,” King said. “2019 was the last downcycle we had, and it was pretty bad. But if you look at some of the operating costs, it was pretty level — especially things like diesel costs. What makes this one so different is the extreme spike in costs … in tandem with the drop in rates. It’s like a double whammy.”

This tension is probably most pronounced for those who bought a new tractor or made the switch to become owner-operators during the market’s boom time, taking on expensive equipment and overhead costs to chase what seemed like guaranteed profit. These drivers may now face a harsh reality that, in the end, inflated rates and high demand were fleeting, and the current market isn’t profitable enough to sustain their businesses.

Many will struggle to make payments on their expensive equipment and wind up with negative equity on it. These are the high stakes involved in making the leap to independent trucking.

Of course, this is not the first time the trucking market has taken a dip. In fact, the freight industry has experienced more than a dozen recessions in the past 50 years. Each freight recession is unique in its own way, but owner-operators tend to struggle to weather these downturns. They’re hit harder and faster than larger carriers and, in some cases, they have no choice but to sell their equipment and leave the industry altogether.

An uncertain future

The owner-operator may be trucking’s best stab at the American dream. For decades, people have targeted it with the goal of financial stability and independence. A successful owner-operator has more direct control of income and hours than most workers in the world. There’s also that human obsession with the open road to consider — ending the day somewhere different than where it started.

Of course, professional drivers face a number of health challenges as a result of the demanding and sedentary nature of the job. The long hours spent behind the wheel, combined with the stress of navigating busy highways and meeting tight delivery deadlines, take a toll on physical and mental well-being.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says truck drivers are twice as likely to suffer from obesity and diabetes as other U.S. workers. They’re also twice as likely to smoke, with one theory being that it helps combat fatigue.

Even if they can secure affordable health care, keeping regular medical visits can prove to be a real challenge when also maintaining the kind of rigorous schedule that makes being unattached worthwhile. Ultimately, the work is sporadic, isolated and, while widely considered essential, tends to go underappreciated.

Although drivers have to study and practice before they earn their license, there’s no such requirement for learning how to prosper in the industry.

Chris Polk’s biggest problem after becoming owner-operator was bookkeeping. Polk was good at picking up and delivering loads and good at generating revenue. But while working as an owner-operator for Landstar — also known as a business capacity owner — he struck out on the accounting front in 2017.

“When it finally blew up and I couldn’t fix it, there was nobody to blame but me,” Polk said.

At the time, he posted about his experience on a Landstar driver Facebook group and wound up getting in touch with Larry Long. In March 2018, Polk joined Long’s Kentucky-based Blue Ribbon Logistical Solutions, which leases about 15 drivers to Landstar Inway.

The company offers truckers a sort of middle ground between being a company driver and an independent owner-operator. In recent years, Polk and Long have built out an 18-month training course for people looking to make the switch, during which time the students work as company drivers until they save up enough money to pay cash for their first truck. The two preach financial responsibility, like buying an older but reliable tractor, rather than winding up with unreasonable financing on a new one.

“Most truck drivers are treated like garbage,” Polk said. “They feel like, ‘Well, look, if I didn’t have to deal with all these corporations, if I didn’t have to deal with this dispatcher, and I could just book my own loads, everything would be OK.’ And that’s kind of true. Except now, when they buy a truck, they’re going into business. Now they have to become all the people they hate. They have to become the maintenance coordinator, the load planner, the dispatcher, the bookkeeper, the accountant. And they can’t do it because they don’t know how.”

Finding a way

In trucking, there seems to be a point when a driver realizes that no other occupation will suit them. That moment varies from person to person, but like anything else, the longer you’re in it, the less likely you are to leave.

Some established truckers like Kim Schwindt, who earned her CDL in 2011 and has been an owner-operator since ’17, tried to quit but couldn’t. She left her job as a company driver in 2013 but came right back after four months in Montana making $9 an hour.

“Trucking’s in the blood,” Schwindt said. “If you’re in trucking and you’ve made it this long, you don’t jump out of the truck.”

Schwindt has certainly had to weather the whirlwind of the last few years. She has also had to contend with health issues. After grossing roughly $230,000 in 2020 and then closer to $280,000 in ’21, she was sidelined for the second half of ’22 with a broken ankle. Her savings got her through the year — but just barely.

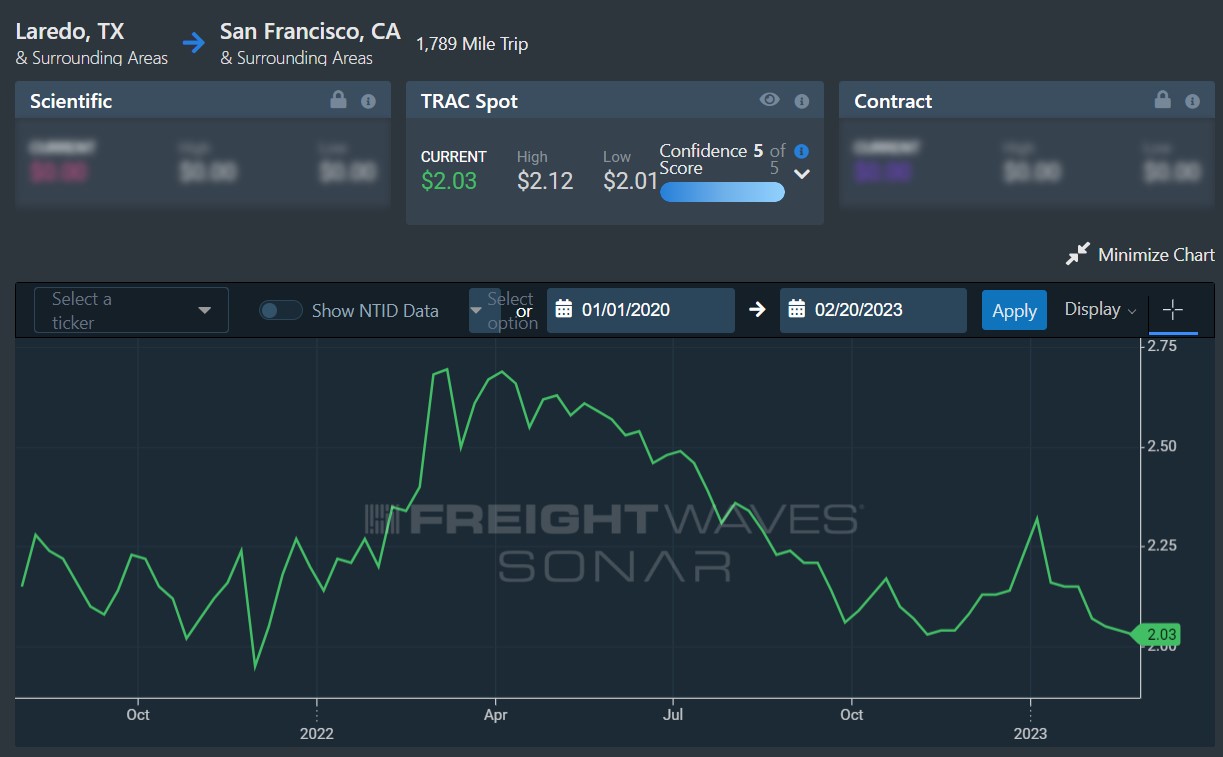

Since returning to the road in January, Schwindt has noticed volume has “drastically declined.” She makes the majority of her money hauling hazmat loads, mostly in the central part of the U.S. While she’s hoping to gross somewhere between $150,000 and $200,000 this year, that will only be after some 10 months on the road, compared to the eight and a half she worked in 2021.

“I’m going to be hustling to get that savings back up,” Schwindt said.

Her ankle is in much better shape these days, but she’s not solo yet. At the moment she’s teamed up with fellow driver Lisa Adams, who can help cut down on long stretches or take over if the injury flares up. Adams is a somewhat less-tenured driver, having only had her CDL since 2018, but she has quickly taken to trucking, even coaxing her husband — previously an engineer — to earn his license. Adams became an owner-operator in late 2019, less than six months before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now both she and Schwindt lease on to Austin, Texas-based carrier Doxa.

Adams worried about bankruptcy when the cost of fuel shot up in 2022. As a newer owner-operator, her first tractor hemorrhaged cash for repairs, and she couldn’t find anywhere to buy a new one. But now she’s having a new truck delivered in the next week and has no plans to leave the industry. In it for the long haul, you could say.

A family affair

For some owner-operators, trucking is a lineage. When Joseph Weah was a boy, he watched his parents run a trucking company. Initially he went to college rather than follow in their footsteps, but he wound up in the trucking industry as a company driver in 2017. Weah and his wife became owner-operators in May 2019.

The pair hauls automotive parts, mostly running through the Midwest into Texas, under the name Trans North America Lines. They have plans to grow the Sugar Land, Texas-based company, but the volatility COVID brought to the market forced them to hold off on adding to the fleet beyond the truck they drive.

Weah has experienced the kind of swings that many others in the survey said they had felt over the past couple years. After everything was shut down in 2020 due to the pandemic, demand shot up, establishing the groundwork for a 2021 that could be characterized as possibly the best ever for owner-operators. Then operational costs started climbing, and in total they haven’t really let up.

In September 2022, Weah started fielding questions about rate concessions, which he agreed to in order to keep the freight, though, of course, that just shrunk his profit margin further. Now, he understands why other drivers have signed on to companies or left the industry. And while he wants to keep running, it’s not a given that he’ll make it, especially since he doesn’t personally believe trucking will see a material turnaround until 2024.

“I could see that becoming a real possibility,” Weah said. “Right now, we’re just faced with so many costs.”

But he and his wife are college educated, so he said they would have at least somewhat of a backup plan if the business went belly-up. That isn’t to say it would be painless.

“Man, it would really be tough,” he said. “My plan getting into this industry was to be able to take the knowledge I gained from my parents and hopefully be able to grow something bigger that they could be proud of.”

That could still happen. And even if it doesn’t — if the worst comes to pass — Weah said he would still likely find his way back to trucking.

“I’d just have to wait out the storm,” he said.”

Read the full article here.

Jim Allen | FreightWaves

Jim Allen | FreightWaves Arcbest

Arcbest