What’s behind the never-ending freight brokerage layoffs

Freight brokerages hired too many employees over 2021 and 2022, and that tide is now turning

In an article posted by Freight Waves, Rachel Premack discusses how the freight brokerage industry is seeing massive increase in layoffs:

“In a time of record-low unemployment, a crucial segment of the supply chain has seen massive job cuts: the freight brokerage industry.

Freight brokerage companies have cut nearly 1,000 jobs in mass layoffs in 2023. Brokers slashed more than 700 payrolls the previous year.

A freight broker is the intermediary between a carrier (or transportation provider, like a truck driver) and a shipper (whoever is trying to move goods, like a retailer or manufacturer). There are also freight forwarders, who handle international shipments and the customs involved.

Such layoffs aren’t surprising to those who have followed supply-chain news the last few years. Through the middle of 2020 to the end of ’21, all modes of freight transportation were unusually hot.

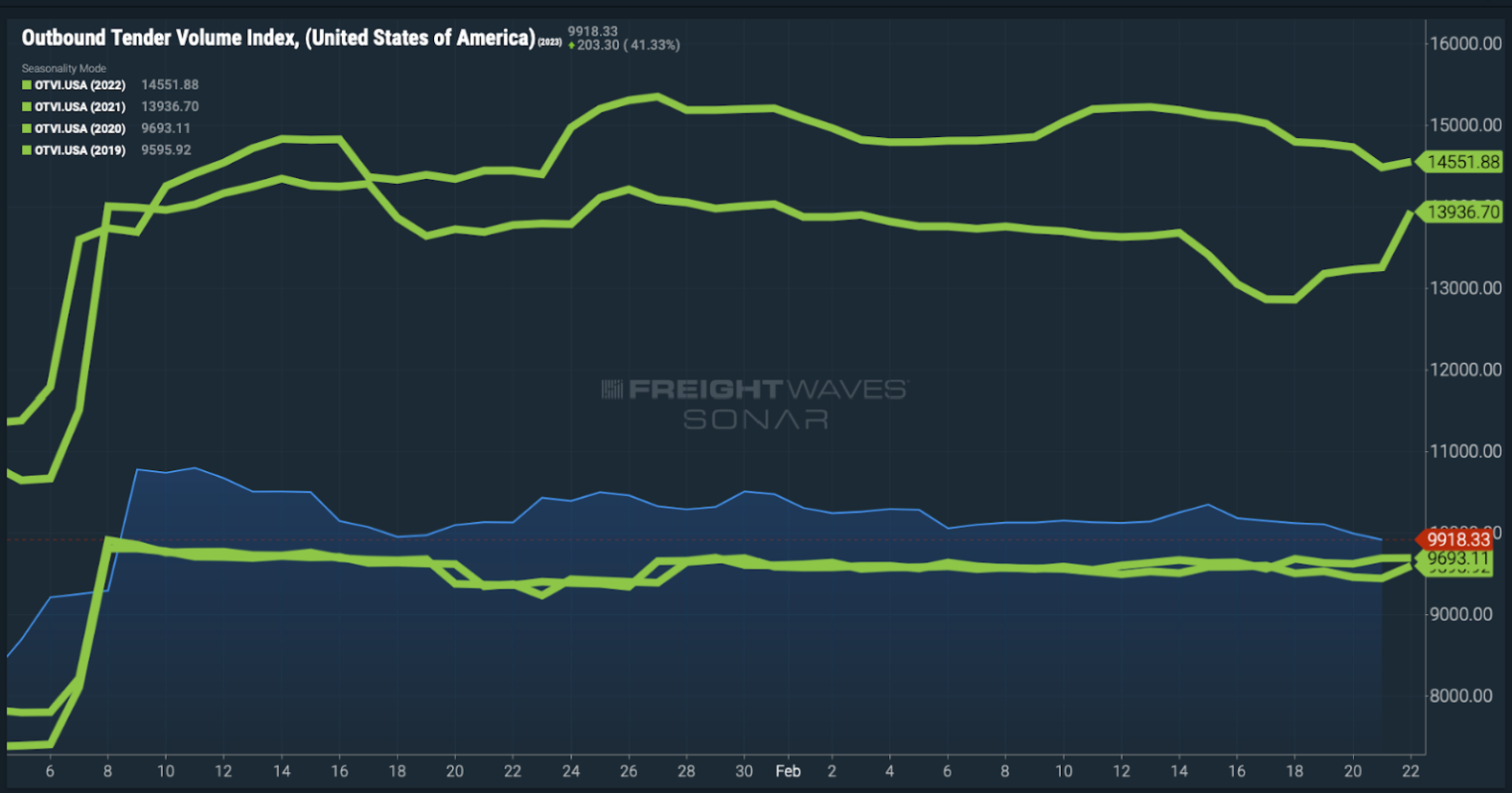

Outbound requests for trucking capacity in the first two months of 2021 and ’22 (top two green lines) were considerably higher than previous years and ’23. (Chart: FreightWaves SONAR) To request a SONAR demo, click here.

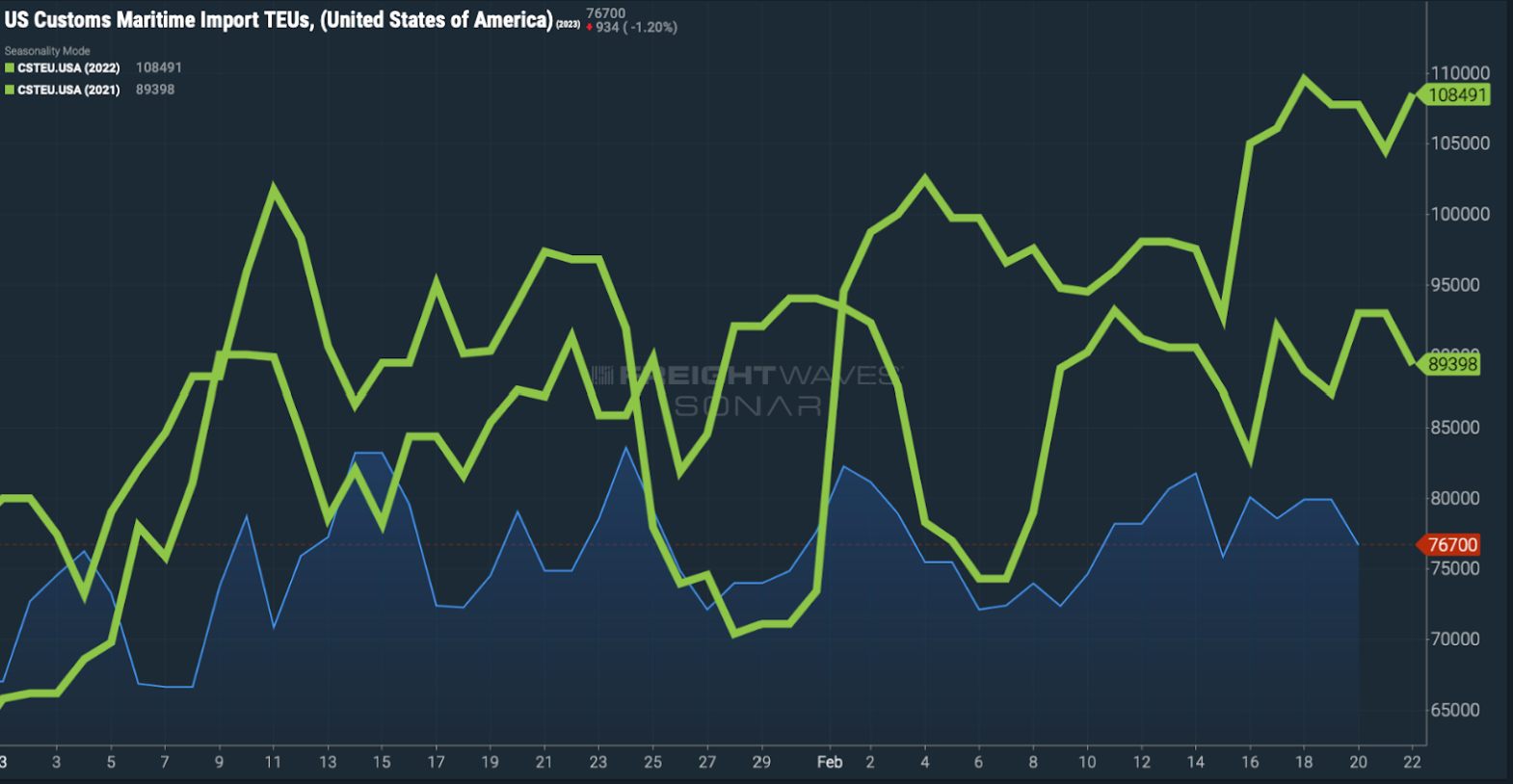

Inbound ocean freight levels were far higher at this time in 2021 and ’22 (green lines) than this year. (Chart: FreightWaves SONAR) To request a SONAR demo, click here.

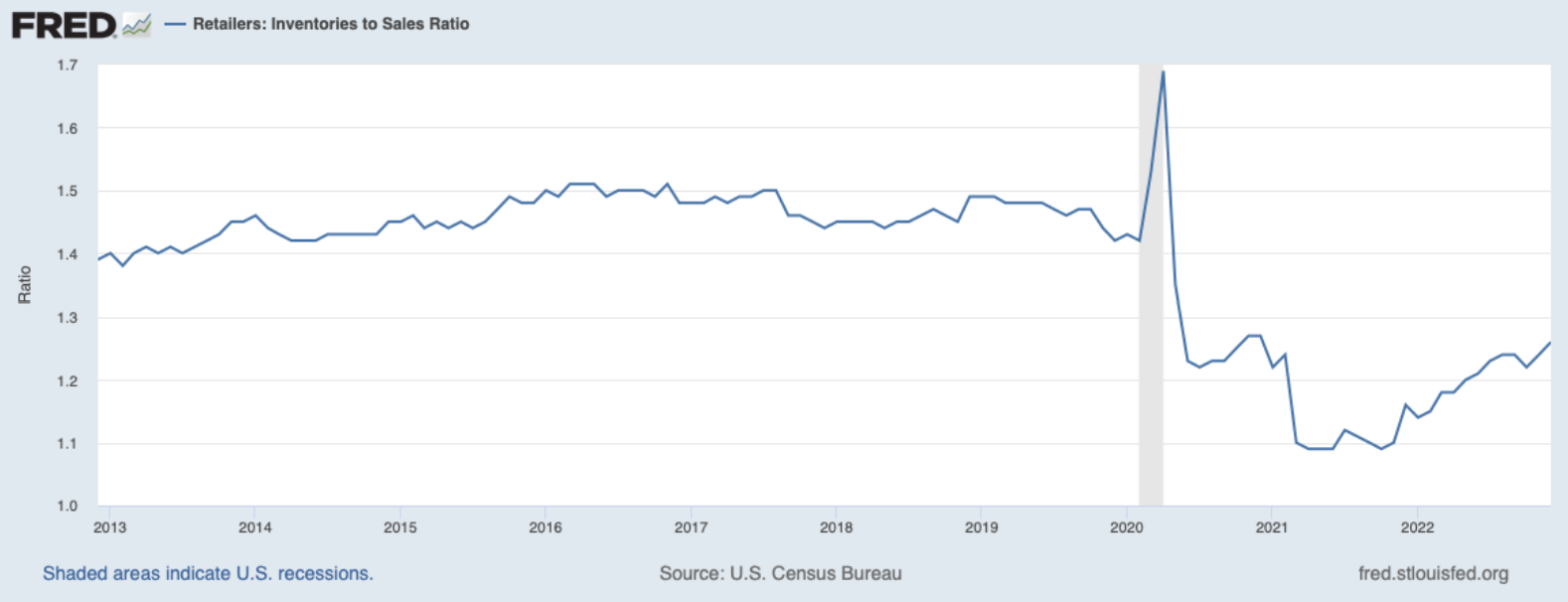

The ratio of inventories to sales dropped to a record low by June 2020, indicating retailers had unusually low levels of merchandise to meet consumer demand. That ratio dipped even lower through 2020 and much of ’21 before beginning to slowly climb up again by November 2021.

Crisis hiring’ in freight brokerage

Such demand for merchandise translated to more freight demand. The amount of shippers calling for more transportation capacity shot up quickly in spring and summer 2020 as consumers began to spend their stimulus bucks and paychecks on durable goods, like exercise bikes and outdoor furniture. However, that freight capacity didn’t reenter the market at the same time.

That meant shippers that normally handled their freight transportation needs in-house had to go to some sort of intermediary, said Benchmark transportation analyst Chris Kuhn.

This made freight brokers unusually rich. C.H. Robinson, the Eden Prairie, Minnesota-based freight brokerage giant, saw its net income jump by 66.7% in 2021 compared to the year before.

“There was just this lack of capacity in the market,” Kuhn said. “That drove prices up to unprecedented levels.”

As a result, third-party freight companies needed to scale up their hiring, too, according to Wells Fargo senior analyst Allison Poliniak-Cusic. C.H. Robinson, for example, grew its overall head count by 43% by the end of 2021 compared to the previous year.

“I would almost call it crisis hiring,” Poliniak-Cusic told FreightWaves. “[They were] building that head count up to manage some of the unusual volatility in the market that they were dealing with at the time to make sure the customers’ issues were met.”

This bull run crashed in spring and summer 2022. Consumer demand began to moderate in early ’22, as some started spending cash on travel or other in-person services while others braced for inflation. In the months following, some of the largest freight brokers and forwarding companies have reduced head counts.

“Now that we’re hopefully past this crisis, your profit at a brokerage is likely lower, [and] your cash flow is a little bit more limited than maybe it had been during the pandemic,” Poliniak-Cusic said. “You have to probably be a little bit more disciplined on investments going forward.”

International looking especially rough

It’s a classic boom-and-bust cycle, but it’s particularly bad for a few types of intermediaries. Freight forwarders, who deal with international shipments, are especially challenged at this time. Expeditors International (NASDAQ: EXPD), one of the largest freight forwarding companies, reported particularly brutal fourth-quarter earnings Tuesday with an operating income down 47% from the year prior.

COVID-19 lockdowns in China and the war in Ukraine have slammed U.S. freight companies that operate overseas.

“We were especially impacted in North Asia, our second-largest geography, as the lingering effects of the lockdowns contributed to the largest declines in our air tonnage and ocean volumes in at least a decade,” Expeditors CEO Jeffrey Musser said on the call with investors.

The spot-vs.-contract tension

There are two markets in trucking. One is the contract market, where truckloads are moved on a prearranged agreement. The second is the spot market, where truck capacity is bid on demand.

The sneaky side of trucking is that you don’t actually have to honor your contracted freight as a truck driver — if you can move more expensive freight on the spot market. And shippers who have contracts with trucking companies, where rates are way above the spot price, can usually break their contracts for as long as they wish to move their loads on the spot market.

(Of course, this is not the best way to build a happy client base, so it’s best to not engage in this too often.)

When the trucking market is hot, spot rates are usually just a few cents below or even slightly above contract rates. That indicates trucking services are in demand, though shippers may also be spending more than they previously planned for freight services. And that cost will likely trickle to the consumer.

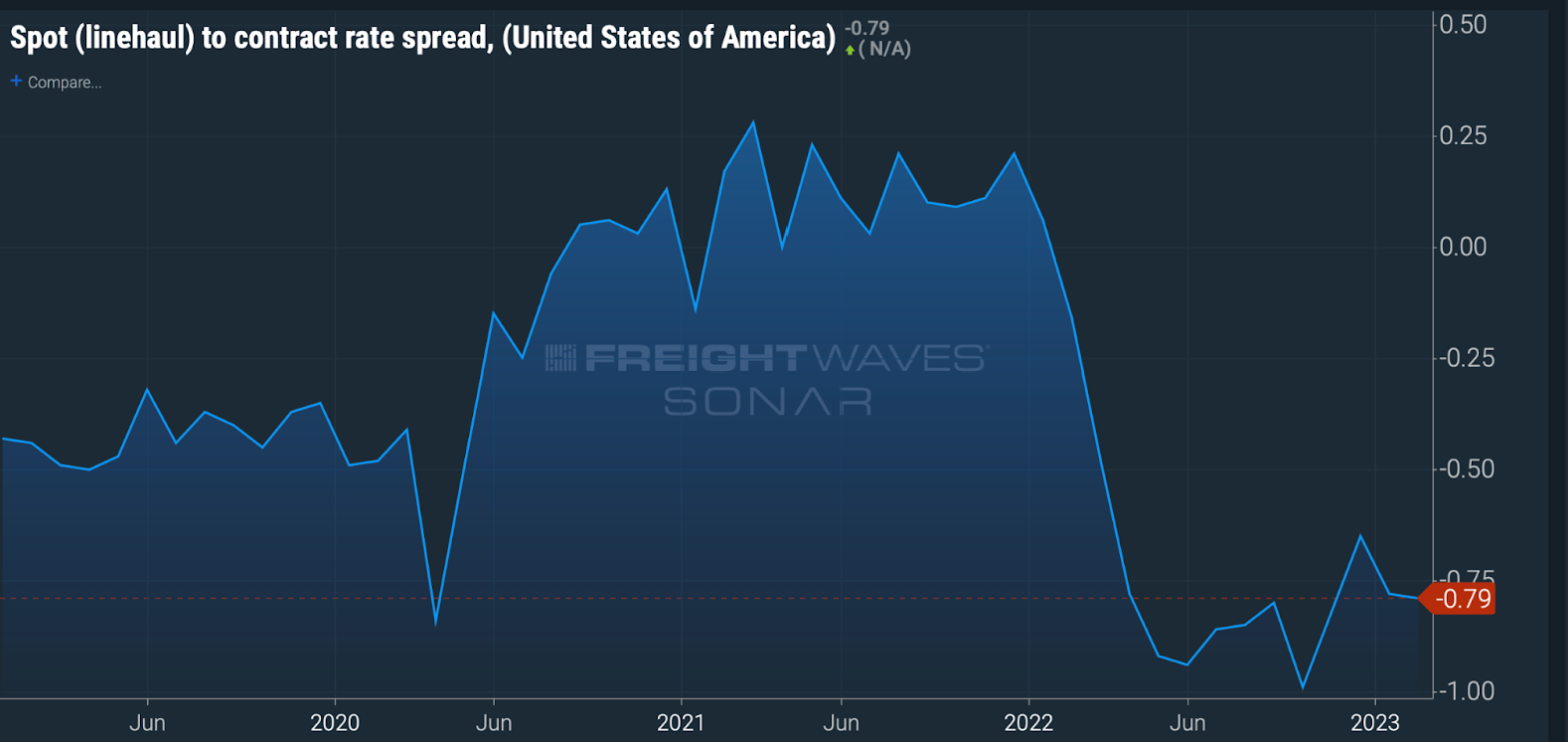

However, since the beginning of 2022, the spread between spot and contract rates have rapidly turned negative.

Here’s the weird thing: Low spot rates are sometimes a win for freight brokers. The spot rate resembles what brokers pay a trucking company. So, if they can still claim the same or a slightly lower rate from the shipper, that means they can earn a larger margin.

However, the market has gotten so rough for trucking that such wins are no longer feasible. Even though margins are sweeter for brokers than they were in 2021, freight volumes are also lower than they were at that time. Brokers might be able to win a larger piece of the proverbial pie, but that pie is getting smaller.

What’s more, there are just way too many brokers for the amount of freight that needs to move right now. There’s a “crisis level” of brokers but a volume of freight that resembles pre-COVID buying patterns.

And that means layoffs.”

Read the full article here.

Cummins | Freight Waves

Cummins | Freight Waves Jim Allen/FreightWaves

Jim Allen/FreightWaves